I’m thinking about Jyoti Singh, known as India’s Daughter as a result of her rape, death, and status as national hero, and I’m hit over and over again with the unwelcome imagining of what it would be like to to be brutally raped to the point that your intestines are falling out and then to have one of your six rapists reach into you and pull them out, separating them from your body and then, while you are alive and conscious, dump you naked in the bushes next to a highway.

In fact, it’s keeping me awake to the point that now, at 3 am, I am finally forced to get out of bed and admit that until I write this down, I will not be able to sleep.

One feeling I’m having is gratitude. I am thankful it wasn’t me. I can feel my own intestines burning and I feel a sense of intactness and relief that I am in bed, alive and, for the moment, safe.

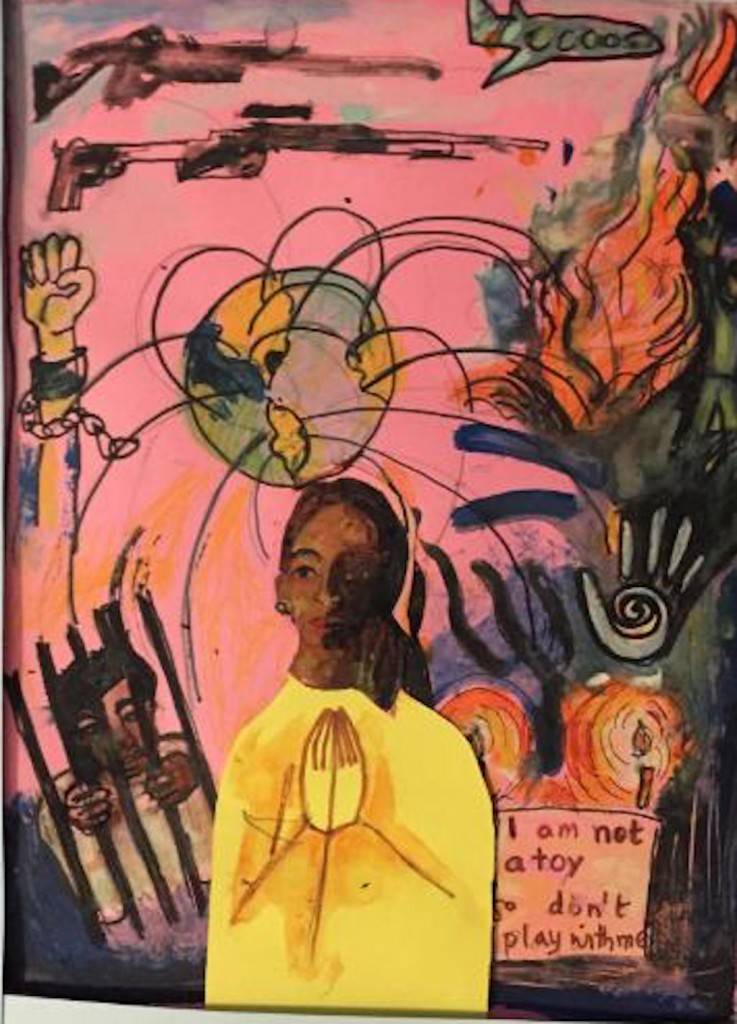

We all know about “man’s inhumanity to man”: We hear about it in the form of slavery, war, mass incarceration, and sexual and domestic violence rates.

As a global community, here’s where we are today:

Slavery

21 million slaves worldwide.

War

500,000 civilian deaths in Iraq.

Mass Incarceration

25% of the world’s incarcerated population (US).

Sexual violence

- 25% of women are raped or sexually assaulted (US).

- 400,000 women per year raped (Congo).

These are the atrocities.

It is our capacity to dehumanize, to experience our fellow human beings as other, that makes atrocities such as the above not only possible, but regular events.

What about the continuum of lesser events that make up our daily lives?

What about the millions who are not slaves, but who work in unsafe and underpaid jobs? Or the difference in employment rates between men and women, white and brown?

What about all the subtle dislocations and violences people live with everyday?

I think of it like this:

- If you’re not white, you’re brown.

- If you’re not straight, you’re gay.

- If you’re poor it’s your fault.

- If you’re rich, you earned it.

It’s also like this:

- White people don’t know they’re white, but they do know you’re brown.

- Straight people don’t know they’re straight, but they do know you’re gay.

If you are gay, brown, or poor, you know that you are gay, brown, or poor, AND you know that the other is straight, white, rich, or all three. One of the problems we face is that privileged people often do not understand the nature and extent of their privilege.

What if straight, white, rich people took a look their status and asked themselves what it means for themselves and for the other?

Not consciously knowing who we are and what that means for us and those around us makes it easier to ignore the dynamics of subtle violences and dislocations. It’s easier, when we haven’t thought it through, to consider ourselves just and justified. If we are willing to consciously consider our status, we can more easily put ourselves in the place of the other.

Until we put ourselves in the place of the other, we can’t really begin to consider the divorces that leave single mothers to fend for themselves in poverty in a country that considers them lazy and morally suspect, if not actual aggressors.

Or what it’s like to know, as a black woman, that you are more likely to be mugged in your lifetime partly because you woke up and your skin was a particular shade of brown.

Or the impact of an unequal access to an education system that makes learning about getting an A so we can succeed, which in our society means to have more.

Having more actually means having more than someone else, and that someone else should be someone who deserves it less. The someone else should be brown, or they should be a woman, or they should be immoral, or they should live far away, picking trash or mining minerals in places we’ve never heard of . . . why?

So the having more doesn’t hurt the ones who have it.

This post was written for you, me, and everyone living together on this earth in honor of Jyoti Singh, Dr. Martin Luther King, whose birthday we’re celebrating this week, and the Dominican friar Xavier Plassat, who lives and works in Brazil, risking his life to end slavery there. The first two heroes were murdered as a result of efforts to live free and make the world a better place. Plassat faces death every day doing the anti-slavery work that he does.

Jyoti Singh fought the odds against women in her country to become a successful medical student, having passed her final exams just before her death in a country that burns women for the crime of being a widow. According to her rapists, she fought to live.

As a result of Jyoti’s life and brutal death, women and men throughout India protested, and put the issue into the public consciousness in a new and powerful way. As a result, rape reporting in India is up 37%.

Dr. King’s achievements are well-known, from his contribution to the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1965 to the legacy of his beautifully intelligent and prolific writing.

Dr. King’s life and work are celebrated each year at this time, and Jyoti has become, in her own country, a national martyr. Plassat has, over the past 20 years, rescued more than 50,000 people from captivity. All three are known internationally. Together, they inspired me to write this post.

My hope is that we can inspire each other, too, to see the darker truths of the world we live in and to do what we can to recognize within ourselves the ways, subtle and not, that we make the people around us other.

Every generation has its villains, heroes, and martyrs–along with those of us who stand by and hope we can stay out of it. We can’t.

As the world has grown smaller, our web of connection has grown larger and more intricate.

We so often take things that aren’t ours to take. We can learn to look at a thing or a situation and see it for what it is and where it came from, whether it was ripped from the belly of the earth, who ripped it, and why. Our cell phones, for example, are made from a limited supply of minerals extracted from the earth by hands made willing only by force.

When next we switch on a cell phone, we can acknowledge and feel grateful for the 14 year-old black boy who, day after day, worked as a slave 1,000 feet below ground, so we could have more. Surely he, like us, enjoys the sun on his face, a full belly, and falling in love.

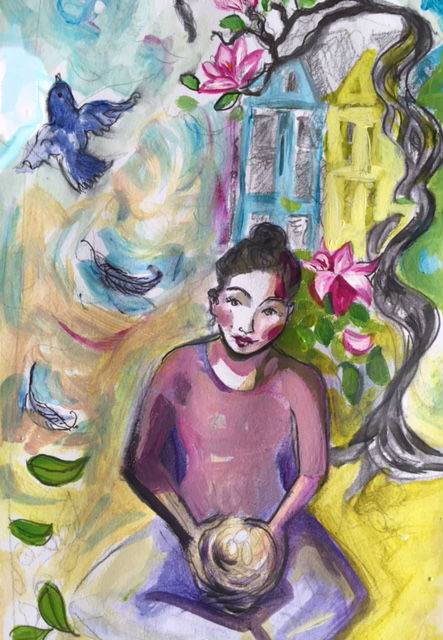

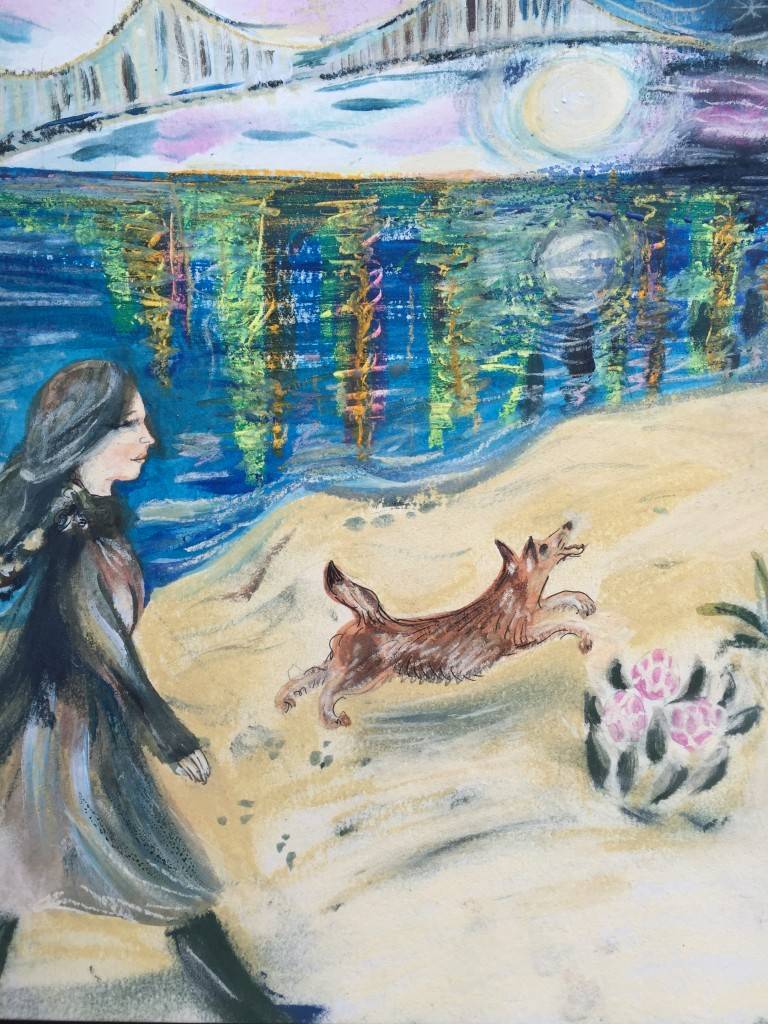

The violence and injustice in our world co-exists with illness, old age, and death, along with birth, breaths of fresh air, bodies running free, and proposed cures for cancer. Artwork surrounds us. Beautiful people and things are everywhere.

Atrocity walks hand-in-hand with heroism on one side and apathy on the other. Life marches on, unstoppable in its quest for itself. The truth is that, as humans, each of us is subject to every form of human suffering. Not one of us is immune.

The facts I’ve shared here have reasons that will be interpreted differently according to character and political orientation. I really don’t know what you should do about the world’s problems as they stand today, or if there is anything you can do about it, given your circumstances.

This post is not a call to action, it is a call for wide-eyed reflection.

-AC

Resources:

Watch India’s Daughter

Read this article about the modern day slave trade.

Listen to this song and read the YouTube comments: